"Gandhi" redirects here. For other uses, see Gandhi (disambiguation).

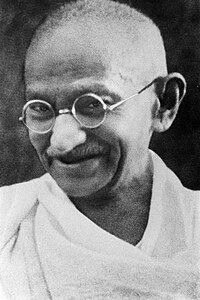

| Mahatma Gandhi | |

|---|---|

|

|

| Born | Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi 2 October 1869 Porbandar, Kathiawar Agency, British India[1] |

| Died | 30 January 1948 (aged 78) New Delhi, Delhi, India |

| Cause of death | Assassination by shooting |

| Resting place | Cremated at Rajghat, Delhi 28.6415°N 77.2483°E |

| Other names | Mahatma Gandhi, Bapu, Gandhiji |

| Ethnicity | Gujarati |

| Education | barrister-at-law |

| Alma mater | Alfred High School, Rajkot, Samaldas College, Bhavnagar, University College, London (UCL) |

| Known for | Leadership of Indian independence movement, philosophy of Satyagraha, Ahimsa or nonviolence, pacifism |

| Movement | Indian National Congress |

| Religion | Hinduism, with Jain influences |

| Spouse(s) | Kasturba Gandhi |

| Children | Harilal Manilal Ramdas Devdas |

| Parent(s) | Putlibai Gandhi (Mother) Karamchand Gandhi (Father) |

| Signature | |

|

|

Born and raised in a Hindu merchant caste family in coastal Gujarat, western India, and trained in law at the Inner Temple, London, Gandhi first employed nonviolent civil disobedience as an expatriate lawyer in South Africa, in the resident Indian community's struggle for civil rights. After his return to India in 1915, he set about organising peasants, farmers, and urban labourers to protest against excessive land-tax and discrimination. Assuming leadership of the Indian National Congress in 1921, Gandhi led nationwide campaigns for easing poverty, expanding women's rights, building religious and ethnic amity, ending untouchability, but above all for achieving Swaraj or self-rule.

Gandhi famously led Indians in challenging the British-imposed salt tax with the 400 km (250 mi) Dandi Salt March in 1930, and later in calling for the British to Quit India in 1942. He was imprisoned for many years, upon many occasions, in both South Africa and India. Gandhi attempted to practise nonviolence and truth in all situations, and advocated that others do the same. He lived modestly in a self-sufficient residential community and wore the traditional Indian dhoti and shawl, woven with yarn hand-spun on a charkha. He ate simple vegetarian food, and also undertook long fasts as a means to both self-purification and social protest.

Gandhi's vision of a free India based on religious pluralism, however, was challenged in the early 1940s by a new Muslim nationalism which was demanding a separate Muslim homeland carved out of India.[7] Eventually, in August 1947, Britain granted independence, but the British Indian Empire[7] was partitioned into two dominions, a Hindu-majority India and Muslim Pakistan.[8] As many displaced Hindus, Muslims, and Sikhs made their way to their new lands, religious violence broke out, especially in the Punjab and Bengal. Eschewing the official celebration of independence in Delhi, Gandhi visited the affected areas, attempting to provide solace. In the months following, he undertook several fasts unto death to promote religious harmony. The last of these, undertaken on 12 January 1948 at age 78,[9] also had the indirect goal of pressuring India to pay out some cash assets owed to Pakistan.[9] Some Indians thought Gandhi was too accommodating.[9][10] Nathuram Godse, a Hindu nationalist, assassinated Gandhi on 30 January 1948 by firing three bullets into his chest at point-blank range.[10]

Indians widely describe Gandhi as the father of the nation.[11][12] His birthday, 2 October, is commemorated as Gandhi Jayanti, a national holiday, and world-wide as the International Day of Nonviolence.

Contents

- 1 Early life and background

- 2 English barrister

- 3 Civil rights activist in South Africa (1893–1914)

- 4 Struggle for Indian Independence (1915–47)

- 5 Assassination

- 6 Principles, practices and beliefs

- 7 Literary works

- 8 Legacy and depictions in popular culture

- 9 See also

- 10 References

- 11 Bibliography

- 12 External links

Early life and background

Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi[13] was born on 2 October 1869[1] to a Hindu Modh Baniya family[14] in Porbandar (also known as Sudamapuri), a coastal town on the Kathiawar Peninsula and then part of the small princely state of Porbandar in the Kathiawar Agency of the Indian Empire. His father, Karamchand Uttamchand Gandhi (1822–1885), served as the diwan (chief minister) of Porbandar state.The Gandhi family originated from the village of Kutiana in what was then Junagadh State.[15] In the late 17th or early 18th century, one Lalji Gandhi moved to Porbandar and entered the service of its ruler, the Rana. Successive generations of the family served as civil servants in the state administration before Uttamchand, Mohandas's grandfather, became diwan in the early 19th century under the then Rana of Porbandar, Khimojiraji.[15][16] In 1831, Rana Khimojiraji died suddenly and was succeeded by his 12-year-old only son, Vikmatji.[16] As a result, Rana Khimojirajji's widow, Rani Rupaliba, became Regent for her son. She soon fell out with Uttamchand and forced him to return to his ancestral village in Junagadh. While in Junagadh, Uttamchand appeared before its Nawab and saluted him with his left hand instead of his right, replying that his right hand was pledged to Porbandar's service.[15] In 1841, Vikmatji assumed the throne and reinstated Uttamchand as his diwan.

In 1847, Rana Vikmatji appointed Uttamchand's son, Karamchand, as diwan after disagreeing with Uttamchand over the state's maintenance of a British garrison.[15] Although he only had an elementary education and had previously been a clerk in the state administration, Karamchand proved a capable chief minister.[17] During his tenure, Karamchand married four times. His first two wives died young, after each had given birth to a daughter, and his third marriage was childless. In 1857, Karamchand sought his third wife's permission to remarry; that year, he married Putlibai (1844–1891), who also came from Junagadh,[15] and was from a Pranami Vaishnava family.[18][19][20][21] Karamchand and Putlibai had three children over the ensuing decade, a son, Laxmidas (c. 1860 – March 1914), a daughter, Raliatbehn (1862–1960) and another son, Karsandas (c. 1866–1913).[22][23]

On 2 October 1869, Putlibai gave birth to her last child, Mohandas, in a dark, windowless ground-floor room of the Gandhi family residence in Porbandar city. As a child, Gandhi was described by his sister Raliat as "restless as mercury...either playing or roaming about. One of his favourite pastimes was twisting dogs' ears."[24] The Indian classics, especially the stories of Shravana and king Harishchandra, had a great impact on Gandhi in his childhood. In his autobiography, he admits that they left an indelible impression on his mind. He writes: "It haunted me and I must have acted Harishchandra to myself times without number." Gandhi's early self-identification with truth and love as supreme values is traceable to these epic characters.[25][26]

The family's religious background was eclectic. Gandhi's father was Hindu[27] and his mother was from a Pranami Vaishnava family. Religious figures were frequent visitors to the home.[28] Gandhi was deeply influenced by his mother Putlibai, an extremely pious lady who "would not think of taking her meals without her daily prayers...she would take the hardest vows and keep them without flinching. To keep two or three consecutive fasts was nothing to her."[29]

In the year of Mohandas's birth, Rana Vikmatji was exiled, stripped of direct administrative power and demoted in rank by the British political agent, after having ordered the brutal executions of a slave and an Arab bodyguard. Possibly as a result, in 1874 Karamchand left Porbandar for the smaller state of Rajkot, where he became a counsellor to its ruler, the Thakur Sahib; though Rajkot was a less prestigious state than Porbandar, the British regional political agency was located there, which gave the state's diwan a measure of security.[30] In 1876, Karamchand became diwan of Rajkot and was succeeded as diwan of Porbandar by his brother Tulsidas. His family then rejoined him in Rajkot.[31]

On 21 January 1879, Mohandas entered the local taluk (district) school in Rajkot, not far from his home. At school, he was taught the rudiments of arithmetic, history, the Gujarati language and geography.[31] Despite being only an average student in his year there, in October 1880 he sat the entrance examinations for Kathiawar High School, also in Rajkot. He passed the examinations with a creditable average of 64 percent and was enrolled the following year.[32] During his years at the high school, Mohandas intensively studied the English language for the first time, along with continuing his lessons in arithmetic, Gujarati, history and geography.[32] His attendance and marks remained mediocre to average, possibly due to Karamchand falling ill in 1882 and Mohandas spending more time at home as a result.[32] Gandhi shone neither in the classroom nor on the playing field. One of the terminal reports rated him as "good at English, fair in Arithmetic and weak in Geography; conduct very good, bad handwriting".

While at high school, Mohandas came into contact with students of other castes and faiths, including several Parsis and Muslims. A Muslim friend of his elder brother Karsandas, named Sheikh Mehtab, befriended Mohandas and encouraged the strictly vegetarian boy to try eating meat to improve his stamina. He also took Mohandas to a brothel one day, though Mohandas "was struck blind and dumb in this den of vice," rebuffed the prostitutes' advances and was promptly sent out of the brothel. As experimenting with meat-eating and carnal pleasures only brought Mohandas mental anguish, he abandoned both and the company of Mehtab, though they would maintain their association for many years afterwards.[33]

In May 1883, the 13-year-old Mohandas was married to 14-year-old Kasturbai Makhanji Kapadia (her first name was usually shortened to "Kasturba", and affectionately to "Ba") in an arranged child marriage, according to the custom of the region.[34] In the process, he lost a year at school.[35] Recalling the day of their marriage, he once said, "As we didn't know much about marriage, for us it meant only wearing new clothes, eating sweets and playing with relatives." However, as was prevailing tradition, the adolescent bride was to spend much time at her parents' house, and away from her husband.[36] Writing many years later, Mohandas described with regret the lustful feelings he felt for his young bride, "even at school I used to think of her, and the thought of nightfall and our subsequent meeting was ever haunting me."[37]

In late 1885, Karamchand died, on a night when Mohandas had just left his father to sleep with his wife, despite the fact she was pregnant.[38] The couple's first child was born shortly after, but survived only a few days. The double tragedy haunted Mohandas throughout his life, "the shame, to which I have referred in a foregoing chapter, was this of my carnal desire even at the critical hour of my father's death, which demanded wakeful service. It is a blot I have never been able to efface or forget...I was weighed and found unpardonably wanting because my mind was at the same moment in the grip of lust.[38][39] Mohandas and Kasturba had four more children, all sons: Harilal, born in 1888; Manilal, born in 1892; Ramdas, born in 1897; and Devdas, born in 1900.[34]

In November 1887, he sat the regional matriculation exams in Ahmedabad, writing exams in arithmetic, history, geography, natural science, English and Gujarati. He passed with an overall average of 40 percent, ranking 404th of 823 successful matriculates.[40] In January 1888, he enrolled at Samaldas College in Bhavnagar State, then the sole degree-granting institution of higher education in the region. During his first and only term there, he suffered from headaches and strong feelings of homesickness, did very poorly in his exams in April and withdrew from the college at the end of the term, returning to Porbandar.[41]

English barrister

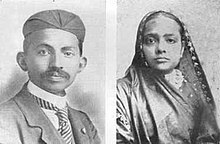

Gandhi and his wife Kasturba (1902)

On 10 August, Gandhi left Porbandar for Bombay (Mumbai). Upon arrival in the port, he was met by the head of the Modh Bania community, who had known Gandhi's family. Having learned of Gandhi's plans, he and other elders warned Gandhi that he would be excommunicated if he did not obey their wishes and remain in India. After Gandhi reiterated his intentions to leave for England, the elders declared him an outcast.[47]

In London, Gandhi studied law and jurisprudence and enrolled at the Inner Temple with the intention of becoming a barrister. His time in London was influenced by the vow he had made to his mother. Gandhi tried to adopt "English" customs, including taking dancing lessons. However, he could not appreciate the bland vegetarian food offered by his landlady and was frequently hungry until he found one of London's few vegetarian restaurants. Influenced by Henry Salt's writing, he joined the Vegetarian Society, was elected to its executive committee,[48] and started a local Bayswater chapter.[20] Some of the vegetarians he met were members of the Theosophical Society, which had been founded in 1875 to further universal brotherhood, and which was devoted to the study of Buddhist and Hindu literature. They encouraged Gandhi to join them in reading the Bhagavad Gita both in translation as well as in the original.[48] Not having shown interest in religion before, he became interested in religious thought.

Gandhi was called to the bar in June 1891 and then left London for India, where he learned that his mother had died while he was in London and that his family had kept the news from him.[48] His attempts at establishing a law practice in Bombay failed because he was psychologically unable to cross-question witnesses. He returned to Rajkot to make a modest living drafting petitions for litigants, but he was forced to stop when he ran foul of a British officer.[20][48] In 1893, he accepted a year-long contract from Dada Abdulla & Co., an Indian firm, to a post in the Colony of Natal, South Africa, a part of the British Empire.[20]

Civil rights activist in South Africa (1893–1914)

Gandhi was 24 when he arrived in South Africa[49] to work as a legal representative for the Muslim Indian Traders based in the city of Pretoria.[50] He spent 21 years in South Africa, where he developed his political views, ethics and political leadership skills.[citation needed]Indians in South Africa were led by wealthy Muslims, who employed Gandhi as a lawyer, and by impoverished Hindu indentured labourers with very limited rights. Gandhi considered them all to be Indians, taking a lifetime view that "Indianness" transcended religion and caste. He believed he could bridge historic differences, especially regarding religion, and he took that belief back to India where he tried to implement it. The South African experience exposed handicaps to Gandhi that he had not known about. He realised he was out of contact with the enormous complexities of religious and cultural life in India, and believed he understood India by getting to know and leading Indians in South Africa.[51]

In South Africa, Gandhi faced the discrimination directed at all coloured people. He was thrown off a train at Pietermaritzburg after refusing to move from the first-class. He protested and was allowed on first class the next day.[52] Travelling farther on by stagecoach, he was beaten by a driver for refusing to move to make room for a European passenger.[53] He suffered other hardships on the journey as well, including being barred from several hotels. In another incident, the magistrate of a Durban court ordered Gandhi to remove his turban, which he refused to do.[54]

These events were a turning point in Gandhi's life and shaped his social activism and awakened him to social injustice. After witnessing racism, prejudice and injustice against Indians in South Africa, Gandhi began to question his place in society and his people's standing in the British Empire.[55]

Gandhi extended his original period of stay in South Africa to assist Indians in opposing a bill to deny them the right to vote. He asked Joseph Chamberlain, the British Colonial Secretary, to reconsider his position on this bill.[50] Though unable to halt the bill's passage, his campaign was successful in drawing attention to the grievances of Indians in South Africa. He helped found the Natal Indian Congress in 1894,[20][52] and through this organisation, he moulded the Indian community of South Africa into a unified political force. In January 1897, when Gandhi landed in Durban, a mob of white settlers attacked him[56] and he escaped only through the efforts of the wife of the police superintendent. However, he refused to press charges against any member of the mob, stating it was one of his principles not to seek redress for a personal wrong in a court of law.[20]

In 1906, the Transvaal government promulgated a new Act compelling registration of the colony's Indian population. At a mass protest meeting held in Johannesburg on 11 September that year, Gandhi adopted his still evolving methodology of Satyagraha (devotion to the truth), or nonviolent protest, for the first time.[57] He urged Indians to defy the new law and to suffer the punishments for doing so. The community adopted this plan, and during the ensuing seven-year struggle, thousands of Indians were jailed, flogged, or shot for striking, refusing to register, for burning their registration cards or engaging in other forms of nonviolent resistance. The government successfully repressed the Indian protesters, but the public outcry over the harsh treatment of peaceful Indian protesters by the South African government forced South African leader Jan Christiaan Smuts, himself a philosopher, to negotiate a compromise with Gandhi. Gandhi's ideas took shape, and the concept of Satyagraha matured during this struggle.

No comments:

Post a Comment