Jagadish Chandra Bose

| Jagadish Chandra Bose জগদীশ চন্দ্র বসু CSI, CIE, FRS |

|

|---|---|

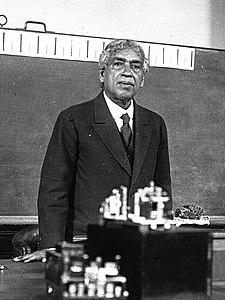

Bose lecturing on the "nervous system" of plants at the Sorbonne in Paris in 1926

|

|

| Born | 30 November 1858 Mymensingh, Bengal Presidency, British India (now Bangladesh) |

| Died | 23 November 1937 (aged 78) Giridih, Bengal Presidency, British India (now Giridih, Jharkhand, India) |

| Residence | Kolkata, Bengal Presidency, British India |

| Citizenship | British Indian |

| Fields | Physics, Biophysics, Biology, Botany, Archaeology, Bengali literature, Bengali science fiction |

| Institutions | University of Calcutta University of Cambridge University of London |

| Alma mater | University of Calcutta Christ's College, Cambridge |

| Academic advisors | John Strutt (Rayleigh) |

| Notable students | Satyendra Nath Bose, Meghnad Saha |

| Known for | Millimetre waves Radio Crescograph Contributions to Plant biology |

| Notable awards | Companion of the Order of the Indian Empire (CIE) (1903) Companion of the Order of the Star of India (CSI) (1911) Knight Bachelor (1917) |

Born in Mymensingh, Bengal Presidency during the British Raj,[10] Bose graduated from St. Xavier's College, Calcutta. He then went to the University of London to study medicine, but could not pursue studies in medicine due to health problems. Instead, he conducted his research with the Nobel Laureate Lord Rayleigh at Cambridge and returned to India. He then joined the Presidency College of University of Calcutta as a Professor of Physics. There, despite racial discrimination and a lack of funding and equipment, Bose carried on his scientific research. He made remarkable progress in his research of remote wireless signalling and was the first to use semiconductor junctions to detect radio signals. However, instead of trying to gain commercial benefit from this invention, Bose made his inventions public in order to allow others to further develop his research.

Bose subsequently made a number of pioneering discoveries in plant physiology. He used his own invention, the crescograph, to measure plant response to various stimuli, and thereby scientifically proved parallelism between animal and plant tissues. Although Bose filed for a patent for one of his inventions due to peer pressure, his reluctance to any form of patenting was well known. To facilitate his research, he constructed automatic recorders capable of registering extremely slight movements; these instruments produced some striking results, such as Bose's demonstration of an apparent power of feeling in plants, exemplified by the quivering of injured plants. His books include Response in the Living and Non-Living (1902) and The Nervous Mechanism of Plants (1926).

Contents

Early life and education

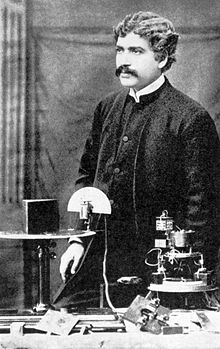

Jagadish Chandra Bose in Royal Institution, London

Bose's education started in a vernacular school, because his father believed that one must know one's own mother tongue before beginning English, and that one should know also one's own people. Speaking at the Bikrampur Conference in 1915, Bose said:

- “At that time, sending children to English schools was an aristocratic status symbol. In the vernacular school, to which I was sent, the son of the Muslim attendant of my father sat on my right side, and the son of a fisherman sat on my left. They were my playmates. I listened spellbound to their stories of birds, animals and aquatic creatures. Perhaps these stories created in my mind a keen interest in investigating the workings of Nature. When I returned home from school accompanied by my school fellows, my mother welcomed and fed all of us without discrimination. Although she was an orthodox old-fashioned lady, she never considered herself guilty of impiety by treating these ‘untouchables’ as her own children. It was because of my childhood friendship with them that I could never feel that there were ‘creatures’ who might be labelled ‘low-caste’. I never realised that there existed a ‘problem’ common to the two communities, Hindus and Muslims.”[12]

Bose wanted to go to England to compete for the Indian Civil Service. However, his father, a civil servant himself, cancelled the plan. He wished his son to be a scholar, who would “rule nobody but himself.”[14] Bose went to England to study Medicine at the University of London. However, he had to quit because of ill health.[15] The odour in the dissection rooms is also said to have exacerbated his illness.[11]

Through the recommendation of Anandamohan Bose, his brother-in-law (sister's husband) and the first Indian wrangler, he secured admission in Christ's College, Cambridge to study Natural Science. He received the Natural Science Tripos from the University of Cambridge and a BSc from the University of London in 1884.[16] Among Bose's teachers at Cambridge were Lord Rayleigh, Michael Foster, James Dewar, Francis Darwin, Francis Balfour, and Sidney Vines. At the time when Bose was a student at Cambridge, Prafulla Chandra Roy was a student at Edinburgh. They met in London and became intimate friends.[11][12] Later he was married to Abala Bose, the renowned feminist, and social worker.[17]

On the second day of a two-day seminar held on the occasion of 150th anniversary of Jagadish Chandra Bose on 28–29 July at The Asiatic Society, Kolkata Professor Shibaji Raha, Director of the Bose Institute, Kolkata told in his valedictory address that he had personally checked the register of the Cambridge University to confirm the fact that in addition to Tripos he received an MA as well from it in 1884.

Joining Presidency College

Photo of Jagadish Bose and his wife Abala Bose, at the home of Edwin Herbert Lewis in Chicago; from the September 1915 issue of The Hindusthanee Student.

Bose was not provided with facilities for research. On the contrary, he was a 'victim of racialism' with regard to his salary.[18] In those days, an Indian professor was paid Rs. 200 per month, while his European counterpart received Rs. 300 per month. Since Bose was officiating, he was offered a salary of only Rs. 100 per month.[19] As a form of protest, Bose refused to accept the salary cheque and continued his teaching assignment for three years without accepting any salary.[18][20] After time, the Director of Public Instruction and the Principal of the Presidency College relented, and Bose's appointment was made permanent with retrospective effect. He was given the full salary for the previous three years in a lump sum.[11]

Presidency College lacked a proper laboratory. Bose had to conduct his research in a small 24-square-foot (2.2 m2) room.[11] He devised equipment for the research with the help of one untrained tinsmith.[18] Sister Nivedita wrote, "I was horrified to find the way in which a great worker could be subjected to continuous annoyance and petty difficulties ... The college routine was made as arduous as possible for him, so that he could not have the time he needed for investigation." After his daily grind, he carried out his research far into the night, in a small room in his college.[18]

Moreover, the policy of the British government for its colonies was not conducive to attempts at original research. Bose spent his own money for making experimental equipment. Within a decade of his joining Presidency College, he emerged a pioneer in the incipient research field of wireless waves.[18]

Radio research

See also: Invention of radio

Bose's 60 GHz microwave apparatus at the Bose Institute, Kolkata, India. His receiver (left) used a galena crystal detector inside a horn antenna and galvanometer to detect microwaves. Bose invented the crystal radio detector, waveguide, horn antenna, and other apparatus used at microwave frequencies.

The first remarkable aspect of Bose's follow up microwave research was that he reduced the waves to the millimetre level (about 5 mm wavelength). He realised the disadvantages of long waves for studying their light-like properties.[21]

During a November 1894 (or 1895[21]) public demonstration at Town Hall of Kolkata, Bose ignited gunpowder and rang a bell at a distance using millimetre range wavelength microwaves.[20] Lieutenant Governor Sir William Mackenzie witnessed Bose's demonstration in the Kolkata Town Hall. Bose wrote in a Bengali essay, Adrisya Alok (Invisible Light), "The invisible light can easily pass through brick walls, buildings etc. Therefore, messages can be transmitted by means of it without the mediation of wires."[21]

Bose's first scientific paper, "On polarisation of electric rays by double-refracting crystals" was communicated to the Asiatic Society of Bengal in May 1895, within a year of Lodge's paper. His second paper was communicated to the Royal Society of London by Lord Rayleigh in October 1895. In December 1895, the London journal the Electrician (Vol. 36) published Bose's paper, "On a new electro-polariscope". At that time, the word 'coherer', coined by Lodge, was used in the English-speaking world for Hertzian wave receivers or detectors. The Electrician readily commented on Bose's coherer. (December 1895). The Englishman (18 January 1896) quoted from the Electrician and commented as follows:

- ”Should Professor Bose succeed in perfecting and patenting his ‘Coherer’, we may in time see the whole system of coast lighting throughout the navigable world revolutionised by a Bengali scientist working single handed in our Presidency College Laboratory.”

Bose went to London on a lecture tour in 1896 and met Italian inventor Guglielmo Marconi, who had been developing a radio wave wireless telegraphy system for over a year and was trying to market it to the British post service. In an interview, Bose expressed disinterest in commercial telegraphy and suggested others use his research work. In 1899, Bose announced the development of a "iron-mercury-iron coherer with telephone detector" in a paper presented at the Royal Society, London.[22]

Place in radio development

Bose conducted his experiments during the years that saw the development of radio into a communication medium. Bose work in radio microwave optics was not related to radio communication[23] but his refinements and writings may have had an influence on other radio inventors.[24][25][26] During this same period from late 1894 on Guglielmo Marconi was working on a radio system specifically designed for wireless telegraphy and by early 1896 was transmitting radio far beyond the short ranges that had been predicted by physics.[27] In May 1895 Russian physicist Alexander Stepanovich Popov, also inspired by Lodges experiment, built a radio wave base lightning detector but did not pursue signalling until later.[25]Bose was the first to use a semiconductor junction to detect radio waves, and he invented various now commonplace microwave components.[25] In 1954, Pearson and Brattain gave priority to Bose for the use of a semi-conducting crystal as a detector of radio waves.[25] Further work at millimetre wavelengths was almost non-existent for nearly 50 years. In 1897, Bose described to the Royal Institution in London his research carried out in Kolkata at millimetre wavelengths. He used waveguides, horn antennas, dielectric lenses, various polarisers and even semiconductors at frequencies as high as 60 GHz;[25] much of his original equipment is still in existence, now at the Bose Institute in Kolkata. A 1.3 mm multi-beam receiver now in use on the NRAO 12 Metre Telescope, Arizona, US, incorporates concepts from his original 1897 papers.[25]

Sir Nevill Mott, Nobel Laureate in 1977 for his own contributions to solid-state electronics, remarked that "J.C. Bose was at least 60 years ahead of his time. In fact, he had anticipated the existence of P-type and N-type semiconductors."[25]

Plant research

His major contribution in the field of biophysics was the demonstration of the electrical nature of the conduction of various stimuli (e.g., wounds, chemical agents) in plants, which were earlier thought to be of a chemical nature. These claims were later proven experimentally.[28] He was also the first to study the action of microwaves in plant tissues and corresponding changes in the cell membrane potential. He researched the mechanism of the seasonal effect on plants, the effect of chemical inhibitors on plant stimuli and the effect of temperature. From the analysis of the variation of the cell membrane potential of plants under different circumstances, he hypothesised that plants can "feel pain, understand affection etc."Study of metal fatigue and cell response

Bose performed a comparative study of the fatigue response of various metals and organic tissue in plants. He subjected metals to a combination of mechanical, thermal, chemical, and electrical stimuli and noted the similarities between metals and cells. Bose's experiments demonstrated a cyclical fatigue response in both stimulated cells and metals, as well as a distinctive cyclical fatigue and recovery response across multiple types of stimuli in both living cells and metals.Bose documented a characteristic electrical response curve of plant cells to electrical stimulus, as well as the decrease and eventual absence of this response in plants treated with anaesthetics or poison. The response was also absent in zinc treated with oxalic acid. He noted a similarity in reduction of elasticity between cooled metal wires and organic cells, as well as an impact on the recovery cycle period of the metal.[29][30]

Science fiction

In 1896, Bose wrote Niruddesher Kahini (The Story of the Missing One), a short story that was later expanded and added to Abyakta (অব্যক্ত) collection in 1921 with the new title Palatak Tuphan (Runaway Cyclone). It was one of the first works of Bengali science fiction.[31][32] It has been translated into English by Bodhisattva Chattopadhyay.[33]Bose and patents

The inventor of "Wireless Telecommunications", Bose was not interested in patenting his invention. In his Friday Evening Discourse at the Royal Institution, London, he made public his construction of the coherer. Thus The Electric Engineer expressed "surprise that no secret was at any time made as to its construction, so that it has been open to all the world to adopt it for practical and possibly moneymaking purposes."[11] Bose declined an offer from a wireless apparatus manufacturer for signing a remunerative agreement. Bose also recorded his attitude towards patents in his inaugural lecture at the foundation of the Bose Institute on 30 November 1917.[citation needed]Legacy

Acharya Bhavan, the residence of J C Bose built in 1902, has been turned to museum.[34]

Many of his instruments are still on display and remain largely usable now, over 100 years later. They include various antennas, polarisers, and waveguides, which remain in use in modern forms today.

To commemorate his birth centenary in 1958, the JBNSTS scholarship programme was started in West Bengal. In the same year, India issued a postage stamp bearing his portrait.[35]

On 14 September 2012, Bose's experimental work in millimetre-band radio was recognised as an IEEE Milestone in Electrical and Computer Engineering, the first such recognition of a discovery in India.[36]

Publications

| Wikisource has original text related to this article: |

Bust of Acharya Jagadish Chandra Bose which is placed in the garden of Birla Industrial & Technological Museum.

- Journals

- Nature published about 27 papers.

- Bose J.C. (1902). "On Elektromotive Wave accompanying Mechanical Disturbance in Metals in Contact with Electrolyte". Proc. Roy. Soc. 70 (459–466): 273–294. doi:10.1098/rspl.1902.0029.

- Bose J.C. (1902). "Sur la response electrique de la matiere vivante et animee soumise ä une excitation.—Deux proceeds d'observation de la reponse de la matiere vivante". Journal de Physique 4 (1): 481–491.

- Books

- Response in the Living and Non-living, 1902

- Plant response as a means of physiological investigation, 1906

- Comparative Electro-physiology: A Physico-physiological Study, 1907

- Researches on Irritability of Plants, 1913

- Physiology of the Ascent of Sap, 1923

- The physiology of photosynthesis, 1924

- The Nervous Mechanisms of Plants, 1926

- Plant Autographs and Their Revelations, 1927

- Growth and tropic movements of plants, 1929

- Motor mechanism of plants, 1928

- Other

- J.C. Bose, Collected Physical Papers. New York, N.Y.: Longmans, Green and Co., 1927

- Abyakta (Bengali), 1922

Honours

- Companion of the Order of the Indian Empire (CIE, 1903)

- Companion of the Order of the Star of India (CSI, 1912)

- Knight Bachelor (1917)

- Fellow of the Royal Society (FRS, 1920)[4]

- Member of the Vienna Academy of Sciences, 1928

- President of the 14th session of the Indian Science Congress in 1927.

- Member of Finnish Society of Sciences and Letters in 1929.

- Member of the League of Nations' Committee for Intellectual Cooperation

- Founding fellow of the National Institute of Sciences of India (now the Indian National Science Academy)

- The Indian Botanic Garden was renamed as the Acharya Jagadish Chandra Bose Indian Botanic Garden on 25 June 2009 in honour of Jagadish Chandra Bose.[37]

Notes

- Page 3597 of Issue 30022. The London Gazette. (17 April 1917). Retrieved 1 September 2010.

- Page 9359 of Issue 28559. The London Gazette. (8 December 1911). Retrieved 1 September 2010.

- Page 4 of Issue 27511. The London Gazette. (30 December 1902). Retrieved 1 September 2010.

- Saha, M. N. (1940). "Sir Jagadis Chunder Bose. 1858–1937". Obituary Notices of Fellows of the Royal Society 3 (8): 2–0. doi:10.1098/rsbm.1940.0001.

- "Bose". Random House Webster's Unabridged Dictionary.

- A versatile genius, Frontline 21 (24), 2004.

- Chatterjee, Santimay and Chatterjee, Enakshi, Satyendranath Bose, 2002 reprint, p. 5, National Book Trust, ISBN 81-237-0492-5

- Sen, A. K. (1997). "Sir J.C. Bose and radio science". Microwave Symposium Digest 2 (8–13): 557–560. doi:10.1109/MWSYM.1997.602854. ISBN 0-7803-3814-6.

- Bose (crater)

- Editorial Board (2013). Sir Jagadish Chandra Bose. Edinburgh, Scotland: Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc. ISBN 9781593392925.

- Mahanti, Subodh. "Acharya Jagadis Chandra Bose". Biographies of Scientists. Vigyan Prasar, Department of Science and Technology, Government of India. Retrieved 12 March 2007.

- Mukherji, pp. 3–10.

- Murshed, Md Mahbub. "Bose, (Sir) Jagadish Chandra". Banglapedia. Asiatic Society of Bangladesh. Retrieved 12 March 2007.

- "Pursuit and Promotion of Science : The Indian Experience" (PDF). Indian National Science Academy. Retrieved 1 October 2013.

- "Jagadish Chandra Bose". People. Calcuttaweb.com. Retrieved 10 March 2007.

- "Bose, Jagadis Chandra (BS881JC)". A Cambridge Alumni Database. University of Cambridge.

- Sengupta, Subodh Chandra and Bose, Anjali (editors), 1976/1998, Sansad Bangali Charitabhidhan (Biographical dictionary) Vol I, (Bengali), p23, ISBN 81-85626-65-0

- Mukherji, pp. 11–13

- Gangopadhyay, Sunil, Protham Alo, 2002 edition, p. 377, Ananda Publishers Pvt. Ltd.. ISBN 81-7215-362-7

- "Jagadish Chandra Bose" (PDF). Pursuit and Promotion of Science: The Indian Experience (Chapter 2). Indian National Science Academy. 2001. pp. 22–25. Retrieved 12 March 2007.

- Mukherji, pp. 14–25

- Bondyopadhyay, P.K. (January 1998). "Sir J. C. Bose's Diode Detector Received Marconi's First Transatlantic Wireless Signal of December 1901 (The "Italian Navy Coherer" Scandal Revisited)". Proceedings of the IEEE 86 (1): 259–285. doi:10.1109/5.658778.

- Sungook Hong, Wireless: From Marconi's Black-box to the Audion, MIT Press – 2001, page 199

- Sungook Hong, Wireless: From Marconi's Black-box to the Audion, MIT Press – 2001, page 22

- Emerson, D. T. (1997). "The work of Jagadis Chandra Bose: 100 years of MM-wave research". IEEE Transactions on Microwave Theory and Research 45 (12): 2267–2273. Bibcode:1997imsd.conf..553E. doi:10.1109/MWSYM.1997.602853. ISBN 9780986488511. reprinted in Igor Grigorov, Ed., Antentop, Vol. 2, No.3, pp. 87–96.

- Jagadish Chandra Bose: The Real Inventor of Marconi’s Wireless Receiver; Varun Aggarwal, NSIT, Delhi, India

- Sungook Hong, Wireless: From Marconi's Black-box to the Audion, MIT Press – 2001, page 21

- Wildon, D. C.; Thain, J. F.; Minchin, P. E. H.; Gubb, I. R.; Reilly, A. J.; Skipper, Y. D.; Doherty, H. M.; O'Donnell, P. J.; Bowles, D. J. (1992). "Electrical signalling and systemic proteinase inhibitor induction in the wounded plant". Nature 360 (6399): 62–5. Bibcode:1992Natur.360...62W. doi:10.1038/360062a0.

- Response in the Living and Non-Living by Sir Jagadis Chandra Bose – Project Gutenberg. Gutenberg.org (3 August 2006). Retrieved 7 July 2012.

- Jagadis Bose (2009). Response in the Living and Non-Living. Plasticine. ISBN 978-0-9802976-9-0.

- "Bengal". The Encyclopedia of Science Fiction. Retrieved 5 September 2014.

- "Symposium at Christ's College to celebrate a genius". University of Cambridge. 27 November 2008. Retrieved 26 January 2009.[dead link]

- Jagadish Chandra Bose. "Runaway Cyclone". Bodhisattva Chattopadhyay. Strange Horizons. Retrieved 5 September 2014.

- Acharya Bhavan Opens Its Doors to Visitors. The Times of India. 3 July 2011.

- "J C Bose: The Scientist Who Proved That Plants Too Can Feel". Phila Mirror: The Indian Philately Journal. 30 November 2010. Retrieved 3 August 2012.

- "First IEEE Milestones in India: The work of J.C. Bose and C.V. Raman to be recognized". the Institute. 7 September 2012. Retrieved 14 September 2012.

- "A new name now for grand old Indian Botanical Gardens". The Hindu. 26 June 2009. Retrieved 26 June 2009.

What an incredible tribute to one of India’s greatest minds—Jagadish Chandra Bose’s contributions to science, especially in wireless communication and plant physiology, are truly inspiring. His humility and refusal to commercialize his work only add to his legacy. For anyone inspired by nature like Bose was, a trip to Darjeeling might be the perfect escape: https://northbengaltourism.com/darjeeling-tour-packages/

ReplyDelete