Brahmagupta

| Brahmagupta | |

|---|---|

|

|

| Born | 598 CE |

| Died | c.670 CE |

| Residence | Bhinmal, present day Rajasthan, India |

| Fields | Mathematics, Astronomy |

| Known for | Zero, modern Number system |

Brahmagupta was the first to give rules to compute with zero. The texts composed by Brahmagupta were composed in elliptic verse, as was common practice in Indian mathematics, and consequently have a poetic ring to them. As no proofs are given, it is not known how Brahmagupta's results were derived.[1]

Life and works

In the Brāhmasphuṭasiddhānta verses 7 and 8 of chapter XXIV state that Brahmagupta composed this text at the age of thirty in Śaka 550 (= 628 CE) during the reign of King Vyāghramukha, we can thus gather that he was born in 598.[2] Commentators refer to him as a great scholar from Bhillamala, a city in the state of Rajasthan of present-day Northwest India.[3] In ancient times Bhillamala (modern Bhinmal) was the seat of power of the Gurjars. His father was Jisnugupta.[4] He likely lived most of his life in Bhillamala during the reign (and possibly under the patronage) of King Vyaghramukha.[5] As a result, Brahmagupta is often referred to as Bhillamalacharya, that is, the teacher from Bhillamala. He was the head of the astronomical observatory at Ujjain, and it was during his tenure there that he wrote his two surviving treatises, both on mathematics and astronomy: the Brahmasphutasiddhanta in 628, and the Khandakhadyaka in 665.[dubious ] The Brahmasphutasiddhanta (Corrected Treatise of Brahma) is arguably his most famous work. The historian al-Biruni (c. 1050) in his book Tariq al-Hind states that the Abbasid caliph al-Ma'mun had an embassy from India, and a book was brought to Baghdad which was translated into Arabic as Sindhind. It is generally presumed that Sindhind is none other than Brahmagupta's Brahmasphuta-siddhanta.[6]Although Brahmagupta was familiar with the works of astronomers following the tradition of Aryabhatiya, it is not known if he was familiar with the work of Bhaskara I, a contemporary.[5] Brahmagupta had a plethora of criticism directed towards the work of rival astronomers, and in his Brahmasphutasiddhanta is found one of the earliest attested schisms among Indian mathematicians. The division was primarily about the application of mathematics to the physical world, rather than about the mathematics itself. In Brahmagupta's case, the disagreements stemmed largely from the choice of astronomical parameters and theories.[5] Critiques of rival theories appear throughout the first ten astronomical chapters and the eleventh chapter is entirely devoted to criticism of these theories, although no criticisms appear in the twelfth and eighteenth chapters.[5]

His Works In Mathematics

Algebra

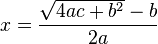

Brahmagupta gave the solution of the general linear equation in chapter eighteen of Brahmasphutasiddhanta,The difference between rupas, when inverted and divided by the difference of the unknowns, is the unknown in the equation. The rupas are [subtracted on the side] below that from which the square and the unknown are to be subtracted.[7]which is a solution for the equation

equivalent to

equivalent to  , where rupas refers to the constants c and e. He further gave two equivalent solutions to the general quadratic equation

, where rupas refers to the constants c and e. He further gave two equivalent solutions to the general quadratic equation18.44. Diminish by the middle [number] the square-root of the rupas multiplied by four times the square and increased by the square of the middle [number]; divide the remainder by twice the square. [The result is] the middle [number].which are, respectively, solutions for the equation

18.45. Whatever is the square-root of the rupas multiplied by the square [and] increased by the square of half the unknown, diminish that by half the unknown [and] divide [the remainder] by its square. [The result is] the unknown.[7]

equivalent to,

equivalent to,18.51. Subtract the colors different from the first color. [The remainder] divided by the first [color's coefficient] is the measure of the first. [Terms] two by two [are] considered [when reduced to] similar divisors, [and so on] repeatedly. If there are many [colors], the pulverizer [is to be used].[7]Like the algebra of Diophantus, the algebra of Brahmagupta was syncopated. Addition was indicated by placing the numbers side by side, subtraction by placing a dot over the subtrahend, and division by placing the divisor below the dividend, similar to our notation but without the bar. Multiplication, evolution, and unknown quantities were represented by abbreviations of appropriate terms.[8] The extent of Greek influence on this syncopation, if any, is not known and it is possible that both Greek and Indian syncopation may be derived from a common Babylonian source.[8]

Arithmetic

Four fundamental operations (addition, subtraction, multiplication and division) were known to many cultures before Brahmagupta. This current system is based on the Hindu Arabic number system and first appeared in Brahmasphutasiddhanta. Brahmagupta describes the multiplication as thus “The multiplicand is repeated like a string for cattle, as often as there are integrant portions in the multiplier and is repeatedly multiplied by them and the products are added together. It is multiplication. Or the multiplicand is repeated as many times as there are component parts in the multiplier”. [9] Indian arithmetic was known in Medieval Europe as "Modus Indoram" meaning method of the Indians. In Brahmasphutasiddhanta, Multiplication was named Gomutrika. In the beginning of chapter twelve of his Brahmasphutasiddhanta, entitled Calculation, Brahmagupta details operations on fractions. The reader is expected to know the basic arithmetic operations as far as taking the square root, although he explains how to find the cube and cube-root of an integer and later gives rules facilitating the computation of squares and square roots. He then gives rules for dealing with five types of combinations of fractions, ,

,  ,

,  ,

,  , and

, and  .[10]

.[10]Series

Brahmagupta then goes on to give the sum of the squares and cubes of the first n integers.12.20. The sum of the squares is that [sum] multiplied by twice the [number of] step[s] increased by one [and] divided by three. The sum of the cubes is the square of that [sum] Piles of these with identical balls [can also be computed].[11]Here Brahmagupta found the result in terms of the sum of the first n integers, rather than in terms of n as is the modern practice.[12]

He gives the sum of the squares of the first n natural numbers as n(n+1)(2n+1)/6 and the sum of the cubes of the first n natural numbers as (n(n+1)/2)².

Zero

Brahmagupta's Brahmasphuṭasiddhanta is the first book that mentions zero as a number[citation needed], hence Brahmagupta is considered the first to formulate the concept of zero. He gave rules of using zero with negative and positive numbers. Zero plus a positive number is the positive number and negative number plus zero is a negative number etc. The Brahmasphutasiddhanta is the earliest known text to treat zero as a number in its own right, rather than as simply a placeholder digit in representing another number as was done by the Babylonians or as a symbol for a lack of quantity as was done by Ptolemy and the Romans. In chapter eighteen of his Brahmasphutasiddhanta, Brahmagupta describes operations on negative numbers. He first describes addition and subtraction,18.30. [The sum] of two positives is positives, of two negatives negative; of a positive and a negative [the sum] is their difference; if they are equal it is zero. The sum of a negative and zero is negative, [that] of a positive and zero positive, [and that] of two zeros zero.He goes on to describe multiplication,

[...]

18.32. A negative minus zero is negative, a positive [minus zero] positive; zero [minus zero] is zero. When a positive is to be subtracted from a negative or a negative from a positive, then it is to be added.[7]

18.33. The product of a negative and a positive is negative, of two negatives positive, and of positives positive; the product of zero and a negative, of zero and a positive, or of two zeros is zero.[7]But his description of division by zero differs from our modern understanding, (Today division by zero is undefinable. That isn't much either).

18.34. A positive divided by a positive or a negative divided by a negative is positive; a zero divided by a zero is zero; a positive divided by a negative is negative; a negative divided by a positive is [also] negative.Here Brahmagupta states that

18.35. A negative or a positive divided by zero has that [zero] as its divisor, or zero divided by a negative or a positive [has that negative or positive as its divisor]. The square of a negative or of a positive is positive; [the square] of zero is zero. That of which [the square] is the square is [its] square-root.[7]

and as for the question of

and as for the question of  where

where  he did not commit himself.[13] His rules for arithmetic on negative numbers and zero are quite close to the modern understanding, except that in modern mathematics division by zero is left undefined.

he did not commit himself.[13] His rules for arithmetic on negative numbers and zero are quite close to the modern understanding, except that in modern mathematics division by zero is left undefined.Diophantine analysis

Pythagorean triples

In chapter twelve of his Brahmasphutasiddhanta, Brahmagupta provides a formula useful for generating Pythagorean triples:12.39. The height of a mountain multiplied by a given multiplier is the distance to a city; it is not erased. When it is divided by the multiplier increased by two it is the leap of one of the two who make the same journey.[14]Or, in other words, if d = mx/(x + 2), then a traveller who "leaps" vertically upwards a distance d from the top of a mountain of height m, and then travels in a straight line to a city at a horizontal distance mx from the base of the mountain, travels the same distance as one who descends vertically down the mountain and then travels along the horizontal to the city.[14] Stated geometrically, this says that if a right-angled triangle has a base of length a = mx and altitude of length b = m + d, then the length, c, of its hypotenuse is given by c = m (1+x) – d. And, indeed, elementary algebraic manipulation shows that a2 + b2 = c2 whenever d has the value stated. Also, if m and x are rational, so are d, a, b and c. A Pythagorean triple can therefore be obtained from a, b and c by multiplying each of them by the least common multiple of their denominators.

Pell's equation

Brahmagupta went on to give a recurrence relation for generating solutions to certain instances of Diophantine equations of the second degree such as (called Pell's equation) by using the Euclidean algorithm. The Euclidean algorithm was known to him as the "pulverizer" since it breaks numbers down into ever smaller pieces.[15]

(called Pell's equation) by using the Euclidean algorithm. The Euclidean algorithm was known to him as the "pulverizer" since it breaks numbers down into ever smaller pieces.[15]The nature of squares:The key to his solution was the identity,[16]

18.64. [Put down] twice the square-root of a given square by a multiplier and increased or diminished by an arbitrary [number]. The product of the first [pair], multiplied by the multiplier, with the product of the last [pair], is the last computed.

18.65. The sum of the thunderbolt products is the first. The additive is equal to the product of the additives. The two square-roots, divided by the additive or the subtractive, are the additive rupas.[7]

and

and

are solutions to the equations

are solutions to the equations  and

and  , respectively, then

, respectively, then

is a solution to

is a solution to  , he was able to find integral solutions to the Pell's equation through a series of equations of the form

, he was able to find integral solutions to the Pell's equation through a series of equations of the form  . Unfortunately, Brahmagupta was not able to apply his solution uniformly for all possible values of N, rather he was only able to show that if

. Unfortunately, Brahmagupta was not able to apply his solution uniformly for all possible values of N, rather he was only able to show that if  has an integer solution for k = ±1, ±2, or ±4, then

has an integer solution for k = ±1, ±2, or ±4, then  has a solution. The solution of the general Pell's equation would have to wait for Bhaskara II in c. 1150 CE.[16]

has a solution. The solution of the general Pell's equation would have to wait for Bhaskara II in c. 1150 CE.[16]Geometry

Brahmagupta's formula

Main article: Brahmagupta's formula

Brahmagupta's most famous result in geometry is his formula for cyclic quadrilaterals.

Given the lengths of the sides of any cyclic quadrilateral, Brahmagupta

gave an approximate and an exact formula for the figure's area,12.21. The approximate area is the product of the halves of the sums of the sides and opposite sides of a triangle and a quadrilateral. The accurate [area] is the square root from the product of the halves of the sums of the sides diminished by [each] side of the quadrilateral.[11]So given the lengths p, q, r and s of a cyclic quadrilateral, the approximate area is

while, letting

while, letting  , the exact area is

, the exact area isTriangles

Brahmagupta dedicated a substantial portion of his work to geometry. One theorem gives the lengths of the two segments a triangle's base is divided into by its altitude:12.22. The base decreased and increased by the difference between the squares of the sides divided by the base; when divided by two they are the true segments. The perpendicular [altitude] is the square-root from the square of a side diminished by the square of its segment.[11]Thus the lengths of the two segments are

.

.He further gives a theorem on rational triangles. A triangle with rational sides a, b, c and rational area is of the form:

Brahmagupta's theorem

Main article: Brahmagupta theorem

Brahmagupta continues,12.23. The square-root of the sum of the two products of the sides and opposite sides of a non-unequal quadrilateral is the diagonal. The square of the diagonal is diminished by the square of half the sum of the base and the top; the square-root is the perpendicular [altitudes].[11]So, in a "non-unequal" cyclic quadrilateral (that is, an isosceles trapezoid), the length of each diagonal is

.

.He continues to give formulas for the lengths and areas of geometric figures, such as the circumradius of an isosceles trapezoid and a scalene quadrilateral, and the lengths of diagonals in a scalene cyclic quadrilateral. This leads up to Brahmagupta's famous theorem,

12.30-31. Imaging two triangles within [a cyclic quadrilateral] with unequal sides, the two diagonals are the two bases. Their two segments are separately the upper and lower segments [formed] at the intersection of the diagonals. The two [lower segments] of the two diagonals are two sides in a triangle; the base [of the quadrilateral is the base of the triangle]. Its perpendicular is the lower portion of the [central] perpendicular; the upper portion of the [central] perpendicular is half of the sum of the [sides] perpendiculars diminished by the lower [portion of the central perpendicular].[11]

Pi

In verse 40, he gives values of π,12.40. The diameter and the square of the radius [each] multiplied by 3 are [respectively] the practical circumference and the area [of a circle]. The accurate [values] are the square-roots from the squares of those two multiplied by ten.[11]So Brahmagupta uses 3 as a "practical" value of π, and

as an "accurate" value of π.

as an "accurate" value of π.Measurements and constructions

In some of the verses before verse 40, Brahmagupta gives constructions of various figures with arbitrary sides. He essentially manipulated right triangles to produce isosceles triangles, scalene triangles, rectangles, isosceles trapezoids, isosceles trapezoids with three equal sides, and a scalene cyclic quadrilateral.After giving the value of pi, he deals with the geometry of plane figures and solids, such as finding volumes and surface areas (or empty spaces dug out of solids). He finds the volume of rectangular prisms, pyramids, and the frustum of a square pyramid. He further finds the average depth of a series of pits. For the volume of a frustum of a pyramid, he gives the "pragmatic" value as the depth times the square of the mean of the edges of the top and bottom faces, and he gives the "superficial" volume as the depth times their mean area.[19]

Trigonometry

Sine table

In Chapter 2 of his Brahmasphutasiddhanta, entitled Planetary True Longitudes, Brahmagupta presents a sine table:2.2-5. The sines: The Progenitors, twins; Ursa Major, twins, the Vedas; the gods, fires, six; flavors, dice, the gods; the moon, five, the sky, the moon; the moon, arrows, suns [...][20]Here Brahmagupta uses names of objects to represent the digits of place-value numerals, as was common with numerical data in Sanskrit treatises. Progenitors represents the 14 Progenitors ("Manu") in Indian cosmology or 14, "twins" means 2, "Ursa Major" represents the seven stars of Ursa Major or 7, "Vedas" refers to the 4 Vedas or 4, dice represents the number of sides of the tradition die or 6, and so on. This information can be translated into the list of sines, 214, 427, 638, 846, 1051, 1251, 1446, 1635, 1817, 1991, 2156, 2312, 1459, 2594, 2719, 2832, 2933, 3021, 3096, 3159, 3207, 3242, 3263, and 3270, with the radius being 3270.[21]

No comments:

Post a Comment