Jagadish Chandra Bose

Jagadish Chandra Bose

জগদীশ চন্দ্র বসু

CSI, CIE, FRS |

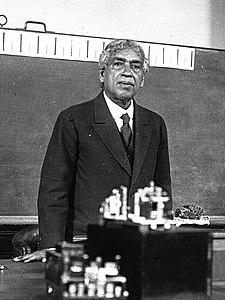

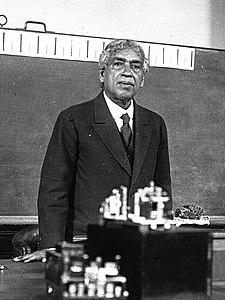

Bose lecturing on the "nervous system" of plants at the Sorbonne in Paris in 1926

|

| Born |

30 November 1858

Mymensingh, Bengal Presidency, British India (now Bangladesh) |

| Died |

23 November 1937 (aged 78)

Giridih, Bengal Presidency, British India (now Giridih, Jharkhand, India) |

| Residence |

Kolkata, Bengal Presidency, British India |

| Citizenship |

British Indian |

| Fields |

Physics, Biophysics, Biology, Botany, Archaeology, Bengali literature, Bengali science fiction |

| Institutions |

University of Calcutta

University of Cambridge

University of London |

| Alma mater |

University of Calcutta

Christ's College, Cambridge |

| Academic advisors |

John Strutt (Rayleigh) |

| Notable students |

Satyendra Nath Bose, Meghnad Saha |

| Known for |

Millimetre waves

Radio

Crescograph

Contributions to Plant biology |

| Notable awards |

Companion of the Order of the Indian Empire (CIE) (1903)

Companion of the Order of the Star of India (CSI) (1911)

Knight Bachelor (1917) |

Sir Jagadish Chandra Bose,

[1] CSI,

[2] CIE,

[3] FRS[4] (

;

[5] Bengali pronunciation: [dʒɔgod̪iʃ tʃɔnd̪ro bosu]; 30 November 1858 – 23 November 1937) was a

Bengali polymath,

physicist,

biologist,

botanist,

archaeologist, as well as an early

writer of science fiction.

[6] He pioneered the investigation of radio and

microwave optics, made very significant contributions to

plant science, and laid the foundations of experimental science in the

Indian subcontinent.

[7] IEEE named him one of the

fathers of radio science.

[8] He is also considered the father of

Bengali science fiction. He also invented the

crescograph.

A crater on the moon has been named in his honour.

[9]

Born in

Mymensingh,

Bengal Presidency during the

British Raj,

[10] Bose graduated from

St. Xavier's College, Calcutta. He then went to the

University of London

to study medicine, but could not pursue studies in medicine due to

health problems. Instead, he conducted his research with the

Nobel Laureate Lord Rayleigh at Cambridge and returned to India. He then joined the

Presidency College of

University of Calcutta as a Professor of Physics. There, despite

racial discrimination

and a lack of funding and equipment, Bose carried on his scientific

research. He made remarkable progress in his research of remote

wireless signalling and was the first to use

semiconductor

junctions to detect radio signals. However, instead of trying to gain

commercial benefit from this invention, Bose made his inventions public

in order to allow others to further develop his research.

Bose subsequently made a number of pioneering discoveries in plant physiology. He used his own invention, the

crescograph, to measure plant response to various

stimuli,

and thereby scientifically proved parallelism between animal and plant

tissues. Although Bose filed for a patent for one of his inventions due

to peer pressure, his

reluctance to any form of patenting

was well known. To facilitate his research, he constructed automatic

recorders capable of registering extremely slight movements; these

instruments produced some striking results, such as Bose's demonstration

of an apparent power of feeling in plants, exemplified by the quivering

of injured plants. His books include

Response in the Living and Non-Living (1902) and

The Nervous Mechanism of Plants (1926).

Early life and education

Sir Jagadish Chandra Bose was born in

Mymensingh,

Bengal Presidency, (present day

Bangladesh)

[10] on 30 November 1858. His father, Bhagawan Chandra Bose, was a

Brahmo and leader of the

Brahmo Samaj and worked as a deputy magistrate/ assistant commissioner in

Faridpur,

[11] Bardhaman and other places.

[12]

Bose's education started in a

vernacular

school, because his father believed that one must know one's own mother

tongue before beginning English, and that one should know also one's

own people. Speaking at the

Bikrampur Conference in 1915, Bose said:

- “At that time, sending children to English schools was an

aristocratic status symbol. In the vernacular school, to which I was

sent, the son of the Muslim attendant of my father sat on my right side,

and the son of a fisherman sat on my left. They were my playmates. I

listened spellbound to their stories of birds, animals and aquatic

creatures. Perhaps these stories created in my mind a keen interest in

investigating the workings of Nature. When I returned home from school

accompanied by my school fellows, my mother welcomed and fed all of us

without discrimination. Although she was an orthodox old-fashioned lady,

she never considered herself guilty of impiety by treating these

‘untouchables’ as her own children. It was because of my childhood

friendship with them that I could never feel that there were ‘creatures’

who might be labelled ‘low-caste’. I never realised that there existed a

‘problem’ common to the two communities, Hindus and Muslims.”[12]

Bose joined the

Hare School in 1869 and then

St. Xavier's School at Kolkata. In 1875, he passed the Entrance Examination (equivalent to school graduation) of

University of Calcutta and was admitted to

St. Xavier's College, Calcutta. At St. Xavier's, Bose came in contact with

Jesuit Father

Eugene Lafont, who played a significant role in developing his interest to natural science.

[12][13] He received a bachelor's degree from

University of Calcutta in 1879.

[11]

Bose wanted to go to England to compete for the

Indian Civil Service.

However, his father, a civil servant himself, cancelled the plan. He

wished his son to be a scholar, who would “rule nobody but himself.”

[14] Bose went to England to study Medicine at the

University of London. However, he had to quit because of ill health.

[15] The odour in the dissection rooms is also said to have exacerbated his illness.

[11]

Through the recommendation of

Anandamohan Bose, his brother-in-law (sister's husband) and the first Indian

wrangler, he secured admission in

Christ's College,

Cambridge to study Natural Science. He received the

Natural Science Tripos from the

University of Cambridge and a BSc from the

University of London in 1884.

[16] Among Bose's teachers at Cambridge were

Lord Rayleigh,

Michael Foster,

James Dewar,

Francis Darwin,

Francis Balfour, and Sidney Vines. At the time when Bose was a student at Cambridge,

Prafulla Chandra Roy was a student at Edinburgh. They met in London and became intimate friends.

[11][12] Later he was married to

Abala Bose, the renowned feminist, and social worker.

[17]

On the second day of a two-day seminar held on the occasion of 150th

anniversary of Jagadish Chandra Bose on 28–29 July at The Asiatic

Society, Kolkata Professor Shibaji Raha, Director of the Bose Institute,

Kolkata told in his valedictory address that he had personally checked

the register of the Cambridge University to confirm the fact that in

addition to Tripos he received an MA as well from it in 1884.

Joining Presidency College

Photo of Jagadish Bose and his wife Abala Bose, at the home of Edwin Herbert Lewis in

Chicago; from the September 1915 issue of

The Hindusthanee Student.

Bose returned to India in 1885, carrying a letter from

Fawcett, the economist to

Lord Ripon,

Viceroy of India. On Lord Ripon's request, Sir Alfred Croft, the

Director of Public Instruction, appointed Bose officiating professor of

physics in

Presidency College. The principal,

C. H. Tawney, protested against the appointment but had to accept it.

[18]

Bose was not provided with facilities for research. On the contrary, he was a 'victim of racialism' with regard to his salary.

[18]

In those days, an Indian professor was paid Rs. 200 per month, while

his European counterpart received Rs. 300 per month. Since Bose was

officiating, he was offered a salary of only Rs. 100 per month.

[19]

As a form of protest, Bose refused to accept the salary cheque and

continued his teaching assignment for three years without accepting any

salary.

[18][20]

After time, the Director of Public Instruction and the Principal of the

Presidency College relented, and Bose's appointment was made permanent

with retrospective effect. He was given the full salary for the previous

three years in a lump sum.

[11]

Presidency College lacked a proper laboratory. Bose had to conduct his research in a small 24-square-foot (2.2 m

2) room.

[11] He devised equipment for the research with the help of one untrained tinsmith.

[18] Sister Nivedita

wrote, "I was horrified to find the way in which a great worker could

be subjected to continuous annoyance and petty difficulties ... The

college routine was made as arduous as possible for him, so that he

could not have the time he needed for investigation." After his daily

grind, he carried out his research far into the night, in a small room

in his college.

[18]

Moreover, the policy of the British government for its colonies was

not conducive to attempts at original research. Bose spent his own money

for making experimental equipment. Within a decade of his joining

Presidency College, he emerged a pioneer in the incipient research field

of wireless waves.

[18]

Radio research

Bose's 60 GHz microwave apparatus at the Bose Institute, Kolkata, India. His receiver

(left) used a

galena crystal detector inside a horn antenna and galvanometer to detect microwaves. Bose invented the crystal radio detector,

waveguide,

horn antenna, and other apparatus used at microwave frequencies.

The Scottish theoretical physicist

James Clerk Maxwell mathematically predicted the existence of

electromagnetic radiation

of diverse wavelengths, but he died in 1879 before his prediction was

experimentally verified. Between 1886 and 1888 German physicist

Heinrich Hertz

published the results of his experiments that showed the existence of

electromagnetic waves in free space. Subsequently, British physicist

Oliver Lodge,

who had also been researching electromagnetic, conducted a

commemorative lecture in August 1894 (after Hertz's death) on the quasi

optical nature of "Hertzian waves" (radio waves) and demonstrated their

similarity to light and vision including reflection and transmission at

distances up to 50 meters. Lodge's work was published it in book form

and caught the attention of scientists in different countries including

Bose in India.

[21]

The first remarkable aspect of Bose's follow up microwave research

was that he reduced the waves to the millimetre level (about 5 mm

wavelength). He realised the disadvantages of long waves for studying

their light-like properties.

[21]

During a November 1894 (or 1895

[21])

public demonstration at Town Hall of Kolkata, Bose ignited gunpowder

and rang a bell at a distance using millimetre range wavelength

microwaves.

[20]

Lieutenant Governor Sir William Mackenzie witnessed Bose's

demonstration in the Kolkata Town Hall. Bose wrote in a Bengali essay,

Adrisya Alok

(Invisible Light), "The invisible light can easily pass through brick

walls, buildings etc. Therefore, messages can be transmitted by means of

it without the mediation of wires."

[21]

Bose's first scientific paper, "On polarisation of electric rays by

double-refracting crystals" was communicated to the Asiatic Society of

Bengal in May 1895, within a year of Lodge's paper. His second paper was

communicated to the Royal Society of London by Lord Rayleigh in October

1895. In December 1895, the London journal the

Electrician (Vol.

36) published Bose's paper, "On a new electro-polariscope". At that

time, the word 'coherer', coined by Lodge, was used in the

English-speaking world for Hertzian wave receivers or detectors. The

Electrician readily commented on Bose's coherer. (December 1895).

The Englishman (18 January 1896) quoted from the

Electrician and commented as follows:

- ”Should Professor Bose succeed in perfecting and patenting his

‘Coherer’, we may in time see the whole system of coast lighting

throughout the navigable world revolutionised by a Bengali scientist

working single handed in our Presidency College Laboratory.”

Bose planned to "perfect his coherer" but never thought of patenting it.

[21]

Diagram of microwave receiver and transmitter apparatus, from Bose's 1897 paper.

Bose went to London on a lecture tour in 1896 and met Italian inventor

Guglielmo Marconi, who had been developing a radio wave

wireless telegraphy

system for over a year and was trying to market it to the British post

service. In an interview, Bose expressed disinterest in commercial

telegraphy and suggested others use his research work. In 1899, Bose

announced the development of a "

iron-mercury-iron coherer with telephone detector" in a paper presented at the

Royal Society, London.

[22]

Place in radio development

Bose conducted his experiments during the years that saw the

development of radio into a communication medium. Bose work in radio

microwave optics was not related to radio communication

[23] but his refinements and writings may have had an influence on other radio inventors.

[24][25][26]

During this same period from late 1894 on Guglielmo Marconi was working

on a radio system specifically designed for wireless telegraphy and by

early 1896 was transmitting radio far beyond the short ranges that had

been predicted by physics.

[27]

In May 1895 Russian physicist Alexander Stepanovich Popov, also

inspired by Lodges experiment, built a radio wave base lightning

detector but did not pursue signalling until later.

[25]

Bose was the first to use a semiconductor junction to detect radio

waves, and he invented various now commonplace microwave components.

[25] In 1954, Pearson and Brattain gave priority to Bose for the use of a semi-conducting crystal as a detector of radio waves.

[25]

Further work at millimetre wavelengths was almost non-existent for

nearly 50 years. In 1897, Bose described to the Royal Institution in

London his research carried out in Kolkata at millimetre wavelengths. He

used waveguides, horn antennas, dielectric lenses, various polarisers

and even semiconductors at frequencies as high as 60 GHz;

[25] much of his original equipment is still in existence, now at the

Bose Institute

in Kolkata. A 1.3 mm multi-beam receiver now in use on the NRAO

12 Metre Telescope, Arizona, US, incorporates concepts from his original

1897 papers.

[25]

Sir Nevill Mott,

Nobel Laureate in 1977 for his own contributions to solid-state

electronics, remarked that "J.C. Bose was at least 60 years ahead of his

time. In fact, he had anticipated the existence of P-type and N-type

semiconductors."

[25]

Plant research

Jagadish Chandra Bose

His major contribution in the field of biophysics was the

demonstration of the electrical nature of the conduction of various

stimuli (e.g., wounds, chemical agents) in plants, which were earlier

thought to be of a chemical nature. These claims were later proven

experimentally.

[28]

He was also the first to study the action of microwaves in plant

tissues and corresponding changes in the cell membrane potential. He

researched the mechanism of the seasonal effect on plants, the effect of

chemical inhibitors on plant stimuli and the effect of temperature.

From the analysis of the variation of the cell

membrane potential of plants under different circumstances, he hypothesised that plants can "feel pain, understand affection etc."

Study of metal fatigue and cell response

Bose performed a comparative study of the fatigue response of various

metals and organic tissue in plants. He subjected metals to a

combination of mechanical, thermal, chemical, and electrical stimuli and

noted the similarities between metals and cells. Bose's experiments

demonstrated a cyclical fatigue response in both stimulated cells and

metals, as well as a distinctive cyclical fatigue and recovery response

across multiple types of stimuli in both living cells and metals.

Bose documented a characteristic electrical response curve of plant

cells to electrical stimulus, as well as the decrease and eventual

absence of this response in plants treated with anaesthetics or poison.

The response was also absent in zinc treated with

oxalic acid.

He noted a similarity in reduction of elasticity between cooled metal

wires and organic cells, as well as an impact on the recovery cycle

period of the metal.

[29][30]

Science fiction

In 1896, Bose wrote

Niruddesher Kahini (The Story of the Missing One), a short story that was later expanded and added to

Abyakta (অব্যক্ত) collection in 1921 with the new title

Palatak Tuphan (Runaway Cyclone). It was one of the first works of

Bengali science fiction.

[31][32] It has been translated into English by Bodhisattva Chattopadhyay.

[33]

Bose and patents

The inventor of "Wireless Telecommunications", Bose was not

interested in patenting his invention. In his Friday Evening Discourse

at the Royal Institution, London, he made public his construction of the

coherer. Thus The Electric Engineer expressed "surprise that no secret

was at any time made as to its construction, so that it has been open to

all the world to adopt it for practical and possibly moneymaking

purposes."

[11]

Bose declined an offer from a wireless apparatus manufacturer for

signing a remunerative agreement. Bose also recorded his attitude

towards patents in his inaugural lecture at the foundation of the

Bose Institute on 30 November 1917.

[citation needed]

Legacy

Acharya Bhavan, the residence of J C Bose built in 1902, has been turned to museum.

[34]

Bose's place in history has now been re-evaluated, and he is credited

with the invention of the first wireless detection device and the

discovery of millimetre length electromagnetic waves and considered a

pioneer in the field of biophysics.

[22]

Many of his instruments are still on display and remain largely

usable now, over 100 years later. They include various antennas,

polarisers, and waveguides, which remain in use in modern forms today.

To commemorate his birth centenary in 1958, the

JBNSTS scholarship programme was started in

West Bengal. In the same year, India issued a postage stamp bearing his portrait.

[35]

On 14 September 2012, Bose's experimental work in millimetre-band

radio was recognised as an IEEE Milestone in Electrical and Computer

Engineering, the first such recognition of a discovery in India.

[36]

Publications

|

Wikisource has original text related to this article:

|

- Journals

- Nature published about 27 papers.

- Bose J.C. (1902). "On Elektromotive Wave accompanying Mechanical Disturbance in Metals in Contact with Electrolyte". Proc. Roy. Soc. 70 (459–466): 273–294. doi:10.1098/rspl.1902.0029.

- Bose J.C. (1902). "Sur la response

electrique de la matiere vivante et animee soumise ä une

excitation.—Deux proceeds d'observation de la reponse de la matiere

vivante". Journal de Physique 4 (1): 481–491.

- Books

- Response in the Living and Non-living, 1902

- Plant response as a means of physiological investigation, 1906

- Comparative Electro-physiology: A Physico-physiological Study, 1907

- Researches on Irritability of Plants, 1913

- Physiology of the Ascent of Sap, 1923

- The physiology of photosynthesis, 1924

- The Nervous Mechanisms of Plants, 1926

- Plant Autographs and Their Revelations, 1927

- Growth and tropic movements of plants, 1929

- Motor mechanism of plants, 1928

- Other

- J.C. Bose, Collected Physical Papers. New York, N.Y.: Longmans, Green and Co., 1927

- Abyakta (Bengali), 1922

Honours

Notes

- Page 3597 of Issue 30022. The London Gazette. (17 April 1917). Retrieved 1 September 2010.

- Page 9359 of Issue 28559. The London Gazette. (8 December 1911). Retrieved 1 September 2010.

- Page 4 of Issue 27511. The London Gazette. (30 December 1902). Retrieved 1 September 2010.

- Saha, M. N. (1940). "Sir Jagadis Chunder Bose. 1858–1937". Obituary Notices of Fellows of the Royal Society 3 (8): 2–0. doi:10.1098/rsbm.1940.0001.

- "Bose". Random House Webster's Unabridged Dictionary.

- A versatile genius, Frontline 21 (24), 2004.

- Chatterjee, Santimay and Chatterjee, Enakshi, Satyendranath Bose, 2002 reprint, p. 5, National Book Trust, ISBN 81-237-0492-5

- Sen, A. K. (1997). "Sir J.C. Bose and radio science". Microwave Symposium Digest 2 (8–13): 557–560. doi:10.1109/MWSYM.1997.602854. ISBN 0-7803-3814-6.

- Bose (crater)

- Editorial Board (2013). Sir Jagadish Chandra Bose. Edinburgh, Scotland: Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc. ISBN 9781593392925.

- Mahanti, Subodh. "Acharya Jagadis Chandra Bose". Biographies of Scientists. Vigyan Prasar, Department of Science and Technology, Government of India. Retrieved 12 March 2007.

- Mukherji, pp. 3–10.

- Murshed, Md Mahbub. "Bose, (Sir) Jagadish Chandra". Banglapedia. Asiatic Society of Bangladesh. Retrieved 12 March 2007.

- "Pursuit and Promotion of Science : The Indian Experience" (PDF). Indian National Science Academy. Retrieved 1 October 2013.

- "Jagadish Chandra Bose". People. Calcuttaweb.com. Retrieved 10 March 2007.

- "Bose, Jagadis Chandra (BS881JC)". A Cambridge Alumni Database. University of Cambridge.

- Sengupta, Subodh Chandra and Bose, Anjali (editors), 1976/1998, Sansad Bangali Charitabhidhan (Biographical dictionary) Vol I, (Bengali), p23, ISBN 81-85626-65-0

- Mukherji, pp. 11–13

- Gangopadhyay, Sunil, Protham Alo, 2002 edition, p. 377, Ananda Publishers Pvt. Ltd.. ISBN 81-7215-362-7

- "Jagadish Chandra Bose" (PDF). Pursuit and Promotion of Science: The Indian Experience (Chapter 2). Indian National Science Academy. 2001. pp. 22–25. Retrieved 12 March 2007.

- Mukherji, pp. 14–25

- Bondyopadhyay,

P.K. (January 1998). "Sir J. C. Bose's Diode Detector Received

Marconi's First Transatlantic Wireless Signal of December 1901 (The

"Italian Navy Coherer" Scandal Revisited)". Proceedings of the IEEE 86 (1): 259–285. doi:10.1109/5.658778.

- Sungook Hong, Wireless: From Marconi's Black-box to the Audion, MIT Press – 2001, page 199

- Sungook Hong, Wireless: From Marconi's Black-box to the Audion, MIT Press – 2001, page 22

- Emerson, D. T. (1997). "The work of Jagadis Chandra Bose: 100 years of MM-wave research". IEEE Transactions on Microwave Theory and Research 45 (12): 2267–2273. Bibcode:1997imsd.conf..553E. doi:10.1109/MWSYM.1997.602853. ISBN 9780986488511. reprinted in Igor Grigorov, Ed., Antentop, Vol. 2, No.3, pp. 87–96.

- Jagadish Chandra Bose: The Real Inventor of Marconi’s Wireless Receiver; Varun Aggarwal, NSIT, Delhi, India

- Sungook Hong, Wireless: From Marconi's Black-box to the Audion, MIT Press – 2001, page 21

- Wildon,

D. C.; Thain, J. F.; Minchin, P. E. H.; Gubb, I. R.; Reilly, A. J.;

Skipper, Y. D.; Doherty, H. M.; O'Donnell, P. J.; Bowles, D. J. (1992).

"Electrical signalling and systemic proteinase inhibitor induction in

the wounded plant". Nature 360 (6399): 62–5. Bibcode:1992Natur.360...62W. doi:10.1038/360062a0.

- Response in the Living and Non-Living by Sir Jagadis Chandra Bose – Project Gutenberg. Gutenberg.org (3 August 2006). Retrieved 7 July 2012.

- Jagadis Bose (2009). Response in the Living and Non-Living. Plasticine. ISBN 978-0-9802976-9-0.

- "Bengal". The Encyclopedia of Science Fiction. Retrieved 5 September 2014.

- "Symposium at Christ's College to celebrate a genius". University of Cambridge. 27 November 2008. Retrieved 26 January 2009.[dead link]

- Jagadish Chandra Bose. "Runaway Cyclone". Bodhisattva Chattopadhyay. Strange Horizons. Retrieved 5 September 2014.

- Acharya Bhavan Opens Its Doors to Visitors. The Times of India. 3 July 2011.

- "J C Bose: The Scientist Who Proved That Plants Too Can Feel". Phila Mirror: The Indian Philately Journal. 30 November 2010. Retrieved 3 August 2012.

- "First IEEE Milestones in India: The work of J.C. Bose and C.V. Raman to be recognized". the Institute. 7 September 2012. Retrieved 14 September 2012.

- "A new name now for grand old Indian Botanical Gardens". The Hindu. 26 June 2009. Retrieved 26 June 2009.

References

Mukherji, Visvapriya,

Jagadish Chandra Bose, second edition,

1994, Builders of Modern India series, Publications Division, Ministry

of Information and Broadcasting, Government of India,